How does one judge a movie’s success? Everybody has their own metric for whether or not a film resonates with them. Maybe it features the most robust of editing, the tightest of scripts, or the strongest performances. In terms of trade publications and studios, their primary metrics for success have been theatrical box office earnings. These earnings are the ticket sales a film receives from theaters, determining how much revenue a film has produced.

The publication Variety began publishing box office earnings in 1922 and continues the practice to this very day. Nowadays, there are numerous online publications devoted to tracking the box office grosses, such as Box Office Mojo.

Really though, in the grand scheme of talking about what makes films good or bad, the box office numbers are minuscule in their insight.

When it comes to talking about film and its qualities, box office numbers do not matter.

Now, when I say the box office numbers do not matter, I don’t mean they matter to nobody. They obviously matter to the filmmakers and the studio. A successful box office gross can lead to more films for a director or a continuation of a franchise. A box office hit means better success for a studio and also determines their future slate.

But those numbers only matter to those involved with the business and have a career at stake. If you are not a filmmaker, producer, studio exec, or shareholder, then, really, what value does the box office gross have for you? Well, for some, box office grosses often become shorthand for trying to stress whether a film is good or bad. And, really, this is such an arbitrary angle to stress.

Because, really, does a film need to make a lot of money to be considered good?

A perfect example of the box office not determining the quality or even popularity of a film can be seen in 1994’s The Shawshank Redemption. This period-prison drama is greatly revered today and has become so mainstream that it has been parodied numerous times. But it wasn’t a big hit at the theater.

The film cost $25 million to make and only made a measly $16 million at the theater due to poor marketing and disinterest by audiences amid more popular films. It was only through VHS rentals and numerous reruns on cable that people started to widely recognize the film as a great prison escape movie.

Think about this: When have you ever heard someone talk about The Shawshank Redemption for its box office gross as a negative? When did you ever hear someone cite Shawshank’s box office to justify why that movie was terrible? And if you did hear that argument, would you care? Would it really change your mind?

More people talk about that film for the performances of Tim Robbins and Morgan Freeman. They talk about its effective use of narration to portray the closed nature of men in prison. They talk about the iconic shots of Robbins playing music over the speaker, the guards discovering his tunnel hidden behind a poster, and the escape into the rain.

Nobody talks about the film being bad because it didn’t sell enough tickets.

Nobody cares about that anymore because most people who catch the film on cable or happen to find it on a streaming channel are not furiously looking up its box office numbers to decide whether or not the movie is good.

Yet there are still many people who use the box office as a means to gauge a film’s worth, even though the worth they are judging is really only valuable to those in the trades.

Some like to cite a box office bomb when talking more about a lesser film. If a film turns out to be bad based on how it was made, some people will often tack on the box office as a factor. But, really, these citations more or less address a film’s popularity than it does the quality. Now, the quality might have been poor enough to lead to bad word of mouth and that could have led to poor ticket sales. Such causation is usually speculated by such statements of poor box office returns.

The problem is that people only seem to talk about the low box office results when they want to highlight the terrible traits of a bad film. How often do you hear someone talk about the bad box office of a good film as a counter?

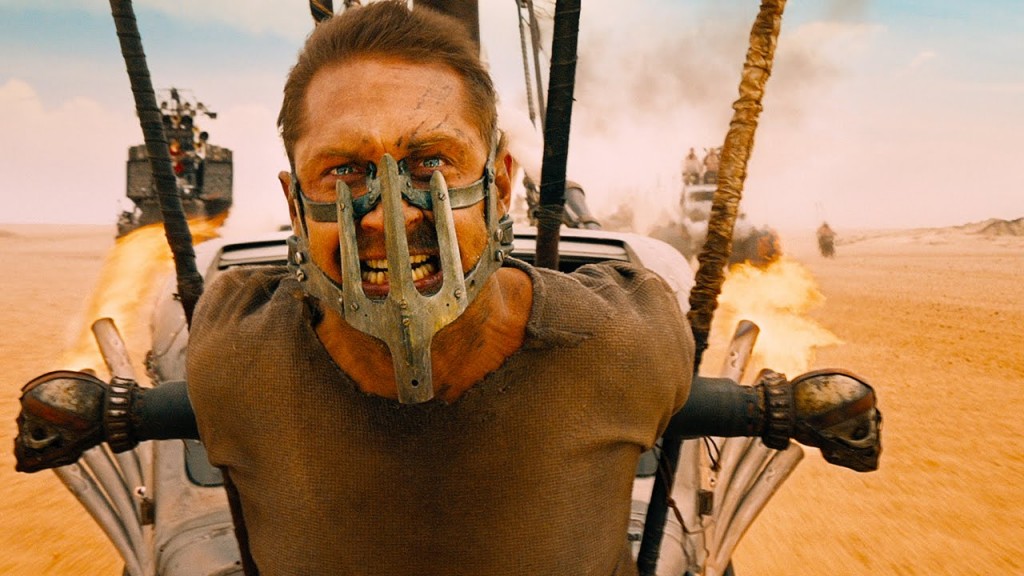

Mad Max: Fury Road is a damn good movie.

But that film actually lost $20-$40 million dollars when comparing the box office gross to the budget. Have you noticed barely anyone talks about this? It’s because there are so many other remarkable things to note about Fury Road. There’s so much fascinating material to observe in its blunt messaging, stylish direction, and exciting convoy chase that something as arbitrary as box office losses are the least interesting things about the film.

Also, box office grosses don’t really work here in justifying a film’s popularity either. Fury Road had a loss and yet it was still greatly revered and even parodied in Space Jam 2. Also in Space Jam 2 were references to The Iron Giant, a film that failed at the box office but has gained enough of a following to appear in two WB films, the other being Ready Player One. The box office losses for Fury Road and The Iron Giant mean nothing compared to how those films were made and why they hold up so well.

The most interesting thing I’ve seen with box office numbers was a podcast betting pool. A host of critics and writers made educated guesses about upcoming films. They then placed bets on which films would perform better than others on certain weekends. But this isn’t really film critique. It’s a game.

It’s the same deal when I’ve seen Rotten Tomatoes percentage predictions. It doesn’t prove whether or not the film is good in terms of how it was made. It just proves how much of a trend you can spot. And, I’m sorry, but argument ad populum is a pretty weak argument for a film’s quality.

This argument is actually more prominent than you may think. I have literally heard a radio show host say that American Sniper deserved the Academy Award for Best Picture because it made more money than all the Best Picture nominations combined, as though that is an actual gauge of whether or not a film is good.

For reference, there already is an award for a film that makes the most money. It’s called the Golden Reel Award and it’s pretty pointless because there’s no suspense about who wins it considering the award is metrically determined.

Perhaps the weirdest citation of box office returns to gauge a film’s worth was with Captain Marvel.

Although it’s not so much citation as it is misreading and improperly observing data. See, there were a lot of people counting on this film to fail. A number of YouTubers constructed narratives for a full month that Captain Marvel was going to flop, based mostly on the fact that they didn’t like the actor Brie Larson.

On opening weekend, however, Captain Marvel made $153 million and, over the course of its run, would make $1.128 billion worldwide. That’s a lot of money even by the standards of Marvel Studios. This did not sit well for those who were predicting a flop, even though all legitimate data on tracking the picture clearly predicted the film would be a success.

A number of angry Marvel fans went about trying to suggest that the numbers were fake. They didn’t believe the $153 million and tried to find proof that it was inaccurate. Their initial response was that the box office results came in on Sunday and those were estimates. Those estimates must’ve been off, they argued.

So, look, the truth is that, yes, box office estimates are not 100% accurate.

Box office websites will often report the weekend earnings early on Sunday with a weekend estimate. The estimates, however, are not random guesses. They’re based on the current income from Friday and Saturday along with the projected foot traffic based on reserved ticket sales and research data about how likely it is for audiences to go see that particular film that weekend.

And, yes, estimates can be off but those estimates are then corrected on Monday when the box office actuals are posted. The actuals tend to be a few million less or more than what was projected but rarely exceed a $5 million difference since estimates are rarely that far off. And FYI the actuals for Captain Marvel turned out to be slightly higher than the estimate.

Some people actually tried to use photographic evidence that the seatings for Captain Marvel screenings were empty at their local movie theater. How could Captain Marvel possibly make over $150 million in its opening weekend when the theater was empty? The answer they wanted was that Disney was either buying up empty theaters or faking box office numbers. The real answer was that this was an unscientific sample size that proves nothing.

Images like these could easily be faked where screens playing lesser films could be captured and framed to be seen as a Captain Marvel screening. It could also be from a morning screening or late-night weekend screening where foot traffic is considerably lower. And even if we took these photos for their word and the screenings were not filled at peak times, that would still not be a sufficient argument.

There are roughly 11,800 movie theaters in the United States. Your one empty theater accounts for 0.008% of the total box office. It is not viable proof that the box office was off by thousands of millions of dollars. I would say this is an outdated tactic for being so easily disproved, but apparently, it’s still being used with films like Shang-Chi.

It would be like if I wanted to declare that Oreo wasn’t America’s best-selling cookie by going to my local grocery store and finding that the packages have not been flying off the shelves. You understand why this logic doesn’t support my claim, right? My one grocery store doesn’t represent an entire national economic growth of a product that is in thousands of retailers.

For the record, Oreo is the best-selling cookie brand but the lumped variety of independent bakeries actually accounts for a much larger profit than that of Oreo. But I actually learned this by looking at economic reports and statistical income analysis articles on the subject. I would never have arrived at that revelation if I did something as stupid as to take pictures at my local grocery store.

And, really, all of this is just a pointless exercise of trying to prove a movie is bad.

If you don’t like the movie, just say you didn’t like it. What point is there in trying to prove that a film is a box office flop?

Full disclosure here, I used to write articles about the weekend box office. I used to fervently track the numbers and write up reports on them, trying to cite patterns in the ticket sales.

And, honestly, I kinda regret it. These articles were not for people involved in the trades who had to keep an eye on the progress of a studio. They were for people who just watch movies. One of the places I briefly wrote for was a women’s lifestyle magazine that primarily posted about beauty and diet tips! Do you think any of those readers care which superhero movie made more money last weekend?

What are non-trade viewers going to get out of such reports?

Will they be led to think Transformers: The Last Knight is a good movie because it made a lot of money? Will they think Parasite is a terrible film because it was never the #1 film at the box office those weekends it played?

All these numbers would really tell you is how likely there is to be a sequel and how popular such a trend would be in terms of film production, an aspect that is secondary to how the film was made and whether or not you enjoyed watching it. That’s the best-case scenario. The worst scenario is that these numbers are used as actual metrics for how good a film is to decide whether or not to watch it. And that’s just gross. Let’s not do that, please.

Talking about box office grosses now is even more arbitrary when considering the circumstances.

The Covid-19 pandemic has restricted much of the nation’s theaters in how they operate. The pandemic also led to the closures of several theaters. And, perhaps the most apparent shift, movies are now sharing same-day online premieres for VOD and streaming services. Not to mention theatrical windows between theaters and VOD have grown all the more narrow.

With all these huge changes to the movie industry, talking about box office numbers the same way we did before the pandemic is bizarre. There are still people talking about Marvel’s Shang-Chi as though it were a disappointment because it only earned $94.67 million over labor day weekend. Some columnists tried to argue that this was not a good opening as most Marvel movies open to over $100 million.

But even if we took the pandemic and the decreased theatrical windows out of the equation, that is still a record broken for a film released on Labor Day weekend. Movies released on that weekend have historically had earnings pretty low. For reference, the previous record-holder was 2007’s Halloween, with a gross of $30.6 million. So Shang-Chi’s $94.67 million is far from what would be considered a disappointment for that release date, even in pre-Covid times.

However, none of this information matters for those who want to make this declaration of box office flops.

They really just want to say that they didn’t like the movie. And, again, if that’s the case, just say you didn’t like the movie. Don’t try to use the box office to justify your feelings for a film especially when you’re clearly ill-equipped to observe box office trends or read data properly.

The box office is not a sufficient determinate of whether or not a film’s quality is good or bad because it’s an observation more from a marketing and business angle than an artistic critique. Box office earnings ultimately hold little critical weight when it comes to discussing what’s on the screen. It only matters if you allow it to matter and nobody has to agree with you on those merits.

“My Spy: The Eternal City” Review

“My Spy: The Eternal City” Review  “Deadpool & Wolverine” Review

“Deadpool & Wolverine” Review  “The Boys: Season Four” Review

“The Boys: Season Four” Review  “The American Society of Magical Negroes” Review

“The American Society of Magical Negroes” Review  “Twisters” Review

“Twisters” Review  “Sausage Party: Foodtopia” Review

“Sausage Party: Foodtopia” Review  “Robot Dreams” Review

“Robot Dreams” Review  “Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire” Review

“Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire” Review